I’ve been losing sleep over this. Not because I’m watching too much news (which I am), but because I always honestly want to understand where everyone’s coming from all the time and lately that’s been tested really hard. We have two videos of people being shot and killed in Minneapolis, and the partisan divide on the explanation of what happens in each of those videos is split straight down the middle, always opposing one another like there are two realities and they are both really that black and white.

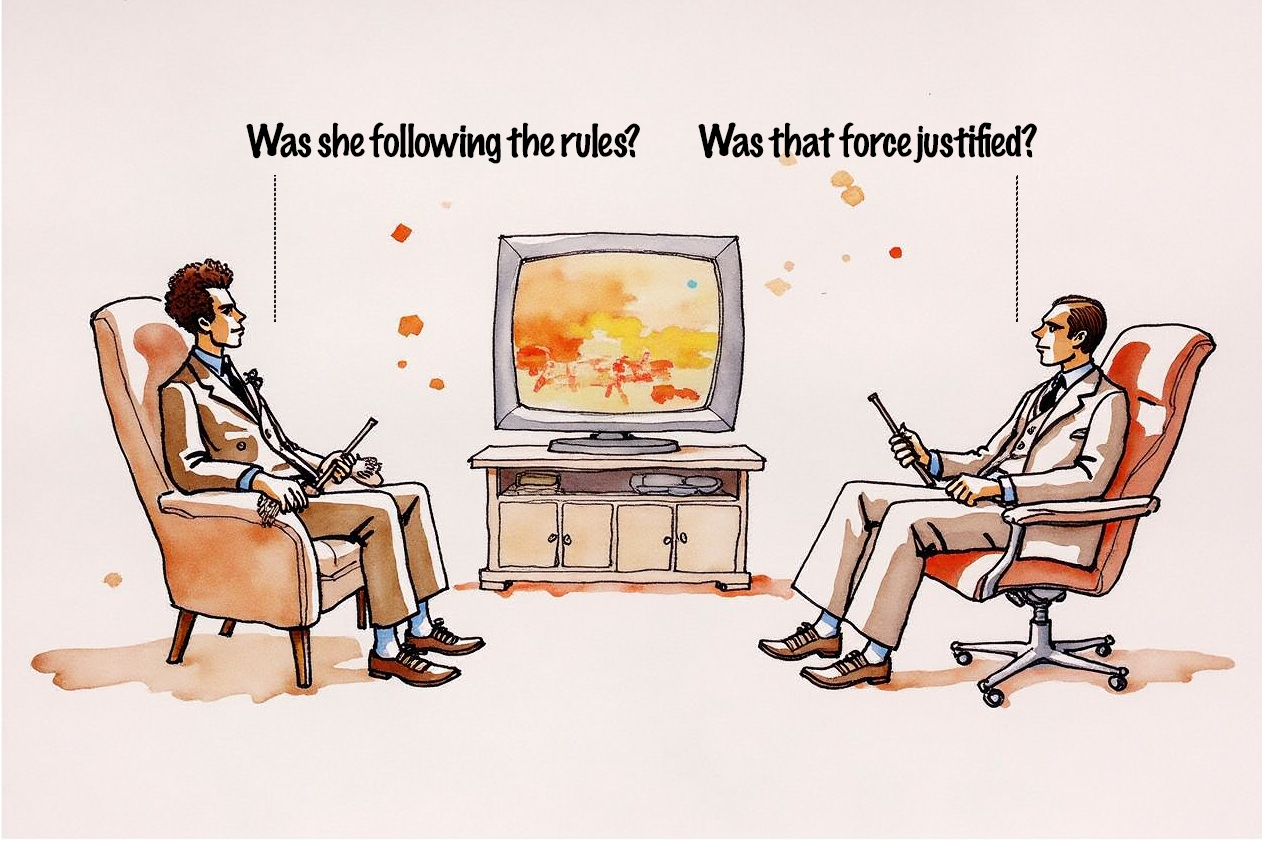

I’ve been trying to wrap my head around how people I love, people I trust, people I respect, people I don’t think are morons, can see the same thing I do and come away thinking something completely opposite. And why does it always align with our political leanings, which makes it overwhelmingly feel like people are just following along and not really thinking it through or listening? The ICE shootings in Minneapolis are the latest example. They illustrate to me that it’s not just politics. It’s something deeper. It’s about our differing moral frameworks, about the lenses through which we see the world and organize our processing of it.

Some people are empathy-first. They look at human harm, suffering, proportionality. They ask, Did this really need to happen? Could someone’s pain have been avoided? They center on the people involved, not the institutions, and feel it in their gut when the answer is no.

Others are authority-first. They instinctively give law enforcement the benefit of the doubt, they value rules and order, they ask, Did they follow the rules? Obedience itself feels like morality to them. They believe strongly in the importance of their country’s foundation and rules and of course in their creator above a lot of things.

It’s exhausting because these aren’t just two opinions. They’re two completely different ways of understanding what’s right and wrong.

On January 7, 2026, Renee Nicole Good, a 37-year-old mother in my home city of Minneapolis, was shot and killed by an ICE agent. Federal officials quickly said it was self-defense, she allegedly tried to use her vehicle as a weapon. DHS and the administration framed it as a split-second threat response, and publicly defended the agent’s actions. To some, that story makes sense. To others, watching the video, it doesn’t. We can’t stop thinking about Renee being charged up on and told with authority to “get the fuck out of the car” while they immediately attack her personal space, attempting to force her door open, while she jumps straight into fight or flight mode and then her life ending in such a fast, split-second decision on two people’s parts.

Local leaders saw it differently than federal leaders. They come from opposite political leanings. Minnesota’s governor and attorney general argued the video doesn’t clearly show Renee threatening anyone. They suggested federal agents may have escalated the situation. State prosecutors are now reviewing the evidence independently, and the Justice Department isn’t pursuing a civil rights investigation. For some, the federal narrative is persuasive. For others, the emotional impact of seeing a civilian shot while trying to leave a tense scene that seemed overboard and not following de-escalation procedures is enough to condemn the use of force. And those narratives collide and harden, leaving no middle ground.

I think about why that happens. Partly, it’s about moral weight. Empathy-focused people are devastated by Renee’s death. They see the federal response as defensive, dismissive, and super cold and hardened toward life itself. And then the Authority-focused people are more likely to give them the benefit of the doubt, emphasizing order and adherence to rules. Partly, it’s about narrative framing. Early claims that Renee was acting like a “domestic terrorist” shaped impressions. When video isn’t crystal clear, people fill in the rest with their moral intuitions. One group sees abuse of power; the other sees justified defensive action. Same moment. Entirely different viewpoints.

It took me years to even notice my own moral lens. I definitely grew up authority-first. Rules, obedience, following orders — I thought that’s what morality was. But little cracks started appearing. Thinking back to watching Mister Rogers as a kid, being reminded to think of others as I was justifying the invasion of Iraq in my mind but then hearing a college professor literally in tears over it because it reminded him of air raids he experienced as a child in England during WWII. Those moments left me unsettled in the strongest way. They made me ask, not “Is the Iraqi government following the rules?” to “Are Iraqi citizens being treated like human beings?” That shift didn’t happen overnight, and it wasn’t easy.

Some might say that was step one of “liberal brainwashing college” but I consider it step one of learning to think critically but that’s kind of cynical, it was simply changing my moral lens, not making me think in some more effective way.

Authority-first morality isn’t born cruel. It’s conditioned. It starts young in strict households, religious structures emphasizing obedience, schools that reward compliance over curiosity, punishment framed as “for your own good.” If authority figures protect you, your brain wires obedience as safety. People who rarely experience arbitrary power like random police stops, humiliation, being disbelieved… they assume institutions are benevolent. Rules feel like anchors; flexibility feels dangerous. Once authority becomes part of your identity, your tribe, your safety net, criticism feels like a personal attack.

And it’s instinctual. When law enforcement is involved, the brain protects itself. Minimize what happened. Reinterpret the video. Search aggressively for justification. Treat the victim as the suspect. It’s not conscious lying; it’s motivated reasoning. Accepting that obedience doesn’t guarantee safety, that institutions can be unjust, that “good people” can uphold harmful systems — that’s identity-shaking. It’s terrifying.

Meanwhile, empathy-first morality asks something different. We have to sit with ambiguity, feel responsibility, hold discomfort without ever getting absolution from some higher power. We see harm and cannot ignore it. We don’t have a higher power to balance things later. We have to own it now. It’s harder. And because empathy is unevenly distributed, shaped by race, class, neighborhood, personal exposure, people experience the same video differently. Someone who’s never been searched or detained sees it abstractly. Someone who has sees it viscerally. Same event. Different lived context. Different emotional truth.

This explains why secular people often lean empathy-first while religious frameworks lean authority-first. Without divine authority, empathy is the only stable moral anchor. Religious morality often flows: God → authority → rules → people. Obedience is virtuous by default. Secular ethics have no shortcut — every rule must justify itself: who does this help, who does it harm? That naturally centers empathy. Secular people tend to universalize it — across race, nationality, legality, social status. Religious morality sometimes includes in-group carve-outs. Even subtly, those distinctions dampen empathy for outsiders.

Religious frameworks also allow moral outsourcing. Suffering may be God’s plan, punishment redemptive, injustice corrected later. Secular ethics offer no escape hatch. If harm occurs, we own it. And we can sit with moral uncertainty in ways authority-first frameworks often cannot. Even if rules were followed, we can feel something is wrong. That sentence is almost impossible for a strict obedience-first mindset.

That’s why policing shows this so clearly. Authority-first lenses see obedience as moral; disobedience invites consequence. Empathy-first lenses see unnecessary suffering as unacceptable. Same event. Entirely different math. And yes, there are exceptions. There are deeply empathetic religious people (Mister Rogers), and cold authoritarian atheists (Donald T***p). It’s not about belief itself. It’s about where legitimacy is sourced: from above/authority or from shared human vulnerability.

Empathy-first morality asks hard things: sit with ambiguity, accept responsibility, feel discomfort without absolution. It asks us to see someone dying, someone being harmed, and say, “This is wrong.” It asks us to notice our institutions can fail. And maybe the hardest part of all: it asks us to keep seeing the humanity in people who may never see it in return.

I used to think morality came from rules and obedience. Now I see it comes from pain, from loss, from listening, from imagining myself in someone else’s shoes. And when I try to understand why people I love see things so differently, I guess I have to remind myself: they are living a different life experience, with different exposures, different emotional truths. And maybe, just maybe, I can try my best to meet them there without losing mine.

But I also know as matter of fact that there are forces at work trying to pit us against one another on purpose, widening the gaps between us, hardening us to what used to feel like normal human reactions. The way people react to the deaths of Renee Good and Alex Pretti, still doesn’t make sense to me. One woman shot while trying to leave a tense encounter, and one ICU nurse shot multiple times in broad daylight as bystander footage shows the situation unfolding in ways that raise real questions about the official narrative and use of force.

I still struggle with how extreme these cases are, how visceral they should feel, how they should draw every ounce of empathy we have and yet, the divides are the same old same old. Some people immediately see the humanity and horror in what happened. Others retreat into rule-following or institutional defense like a shield. And, heartbreakingly, some I care about fall on every side of that line.

That doesn’t make anyone stupid or bad. It means we’re all shaped by our experiences, our fears, our communities, our media, and the moral languages we grew up speaking. But it does make it urgent that we come to terms with how and why we see things so differently. Not so we can win arguments, but so we don’t lose our collective capacity for empathy entirely.

Because if we can’t even agree that a life lost in these circumstances should give everyone pause, then we’ve already lost something deeper than any policy fight. We’ve lost the simple, human instinct to care about one another.