Fence Lines and False Prophets

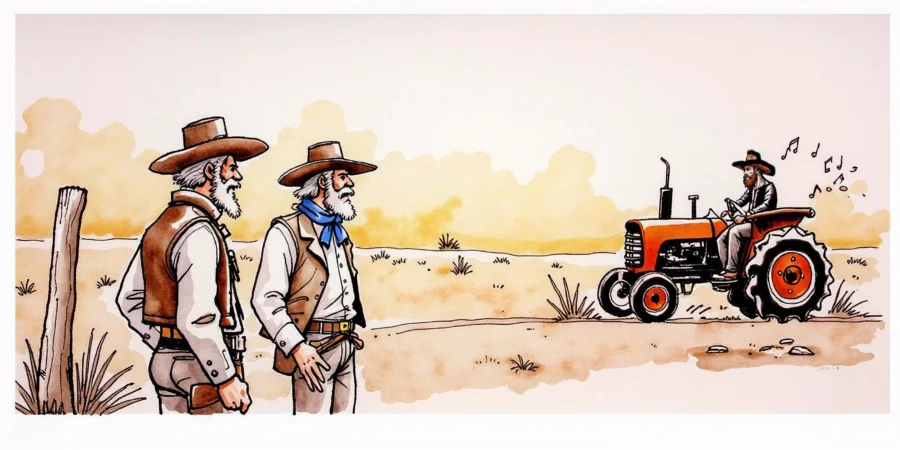

The old cowboys gathered along the fence every morning like it was church and none of them had ever missed a service. Coffee steamed from dented thermoses, breath fogged the air, and spit hit dirt with the kind of accuracy that only comes from repetition and boredom.

They watched him work the south field.

He moved steadily, gloved hands confident as he pulled wire tight and secured it, boots planted in soil he knew better than most people knew their own kitchens. His hat brim shaded his eyes, and his head bobbed faintly, not to birdsong or wind through grass, but to something heavier. Louder. More deliberate.

One of the old cowboys said to the other “How you like having this character farming next door to you? Makes a lot of damn noise!”

Slipknot growled from the stereo system of his tractor.

“That ain’t even music,” Earl said, squinting, “It’s just screaming and shit.”

“Sounds like a tractor dyin’ in hell,” Hank agreed.

“Boy needs Willie Nelson,” Earl added. “Needs to calm down.”

“Willie Nelson is a pot smoking liberal.” Hank replied.

Earl lashed back with an annoyed look “Oh shut up with that bullshit, not everything’s about your damn political party. Willie Nelson is the greatest country musician there ever was and is entitled to smoke grass and tell it how he sees it!”

Which of course turned into a heated, voice-raised, political argument between the men, as their conversations often did.

But the heavy metal cowboy didn’t hear them. Or maybe he did and had long ago learned the difference between sound and meaning. The music wasn’t anger. It was structure. It held his thoughts in place while his hands did what needed doing.

The cows nearby stared at nothing in particular, chewing methodically. They did not care about genre. They did not care about opinions. In many ways, they were the smartest ones there.

Earl cupped his hands and yelled, “HEY! YOU KNOW WILLIE NELSON’S STILL ALIVE, RIGHT?”

The cowboy looked over. “That’s good news,” he said evenly. “He’s metal!”

Earl looked to Hank, “The fuck’s that mean?”

Hank shook his head, and said “Boy’s gonna end up gettin’ his ass kicked by some real cowboys.”

That was when Hank asked it, casual and careless.

“So what are you tryin’ to be, son? Some kinda city boy?”

The question followed him home.

Noise as a Compass

That night, the farmhouse felt too quiet.

He sat at the kitchen table, beer sweating rings into the wood, Avenged Sevenfold humming low through speakers older than most of the men who judged him. The fridge rattled when the bass hit.

“A city boy, huh?” he thought. There was a concert he read about coming up that he wanted to check out. It would definitely be a loud one. Loud enough to shut his head up.

No, he didn’t want to be a city boy. He didn’t want anything the city promised. He just wanted to know if there were other people who understood that loud music didn’t mean chaos—it meant focus.

He took another sip, stared at the ticketmaster page for buying the tickets, and nodded to himself.

“Alright,” he muttered. “Let’s check it out.”

Is This a Bit?

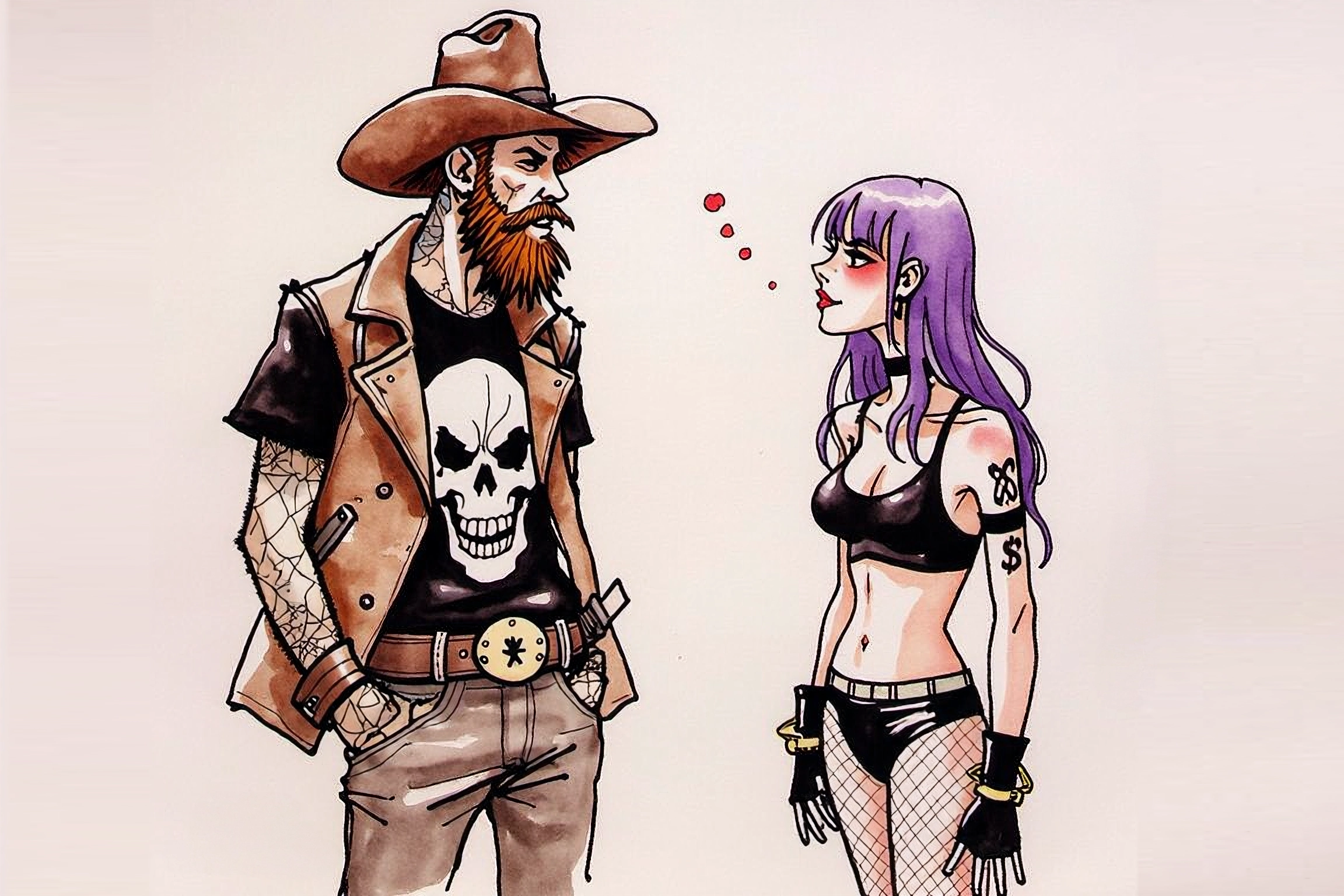

She noticed him immediately.

You couldn’t not.

The venue was packed wall to wall with black T-shirts, spikes, chains, eyeliner thick enough to count as structural support. And then there he was—boots dusty, jeans worn soft, a cowboy hat that looked like it had seen real weather.

She nudged her friend. “Tell me that’s ironic.”

Her friend squinted. “If it is, he’s committing hard.”

She intercepted him near the bar.

“Hon,” she said, “are you lost?”

He looked at her like he’d been genuinely confused by the question. “No, ma’am. I followed the noise.”

That did something to her.

They shouted introductions over the opening band. When he told her he lived on a farm, she assumed he was joking.

“With cows?” she yelled.

“Yes. Several.”

“And you listen to metal while… cowboying?”

He smiled. “Cows don’t mind.”

She laughed before she could stop herself.

When he invited her to come see it sometime, she agreed with enough sarcasm to protect her dignity.

Three days later, she couldn’t stop thinking about him, the sarcasm turned to curiosity, and it won.

Gravel Roads, Ribeyes, and Low Expectations

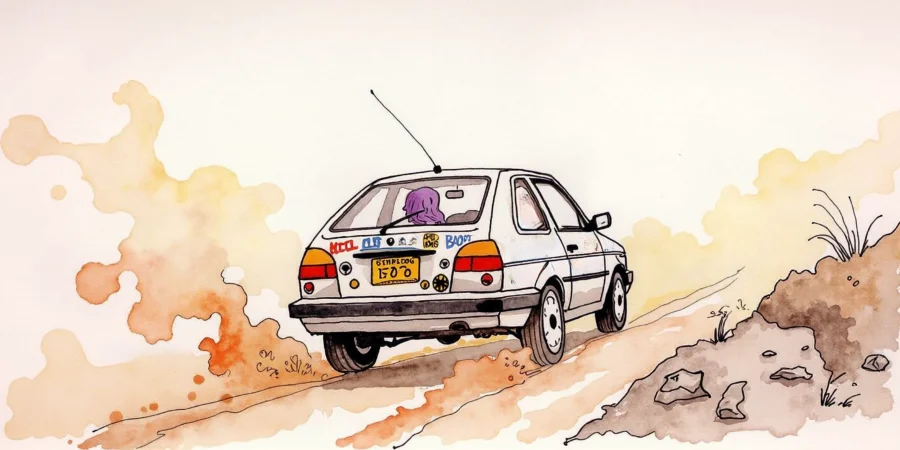

Her Jetta hated the gravel road.

The way it fishtailed slightly, like it was offended by the very concept of uneven terrain. Her car crept forward, suspension complaining loudly, tires crunching rocks with a tone that suggested this was not what it had been engineered for.

The heavy metal cowboy was out in the yard and walked up to her car as she pulled up. He smiled when he saw who it was, it didn’t take long to figure out with her purple hair blowing in the wind. She rolled down the window and leaned out, squinting down the road.

“If I die out here,” she yelled, “I’m haunting your barn.”

He leaned against the fence post, arms crossed, amused.

“Cows could use the company,” he called back.

She pulled up beside him and shut the engine off like it might try to escape if given the chance. She stepped out, her combat boots immediately dusted, and looked around with the guarded skepticism of someone expecting banjos or a crime documentary twist.

Instead, she found quiet.

The barn doors were straight. The fences were intact. The animals were calm, heavy with the confidence of creatures who had never been rushed or yelled at unnecessarily. The garden sat in tidy rows, impossibly green, like someone had taken their time on purpose.

“This is…” she said slowly, scanning the place.

“Not what you pictured?” he offered.

“I pictured more chaos,” she admitted. “And possibly a meth problem.”

“Different farm,” he said. “Left turn two miles back.”

She laughed, tension easing.

He cooked for her like it mattered. Not fancy—never fancy—but intentional. Ribeyes from his own cattle, potatoes from the garden, butter melted slow. He didn’t talk much while cooking, but he didn’t rush either. He worked like the act itself deserved respect.

They ate at the small kitchen table, windows open, night air drifting in.

“This cow,” he said, casually flipping his fork, “used to side-eye me.”

She paused mid-bite. “You’re telling me I’m eating a judgmental cow.”

“I won,” he said.

She stayed longer than she meant to. Long enough that the stars came out thick and unapologetic. Long enough that she stopped checking her phone. Long enough that leaving felt like giving something up.

She drove home that night with the windows down and the radio off, surprised by how quiet felt good instead of empty.

The Town Notices

The town noticed her immediately.

She felt it in the way conversations paused when she walked into the general store. In the way eyes flicked to her tattoos, then away, like they might be contagious. Men smiled too politely. Women didn’t smile at all.

“You lost?” the clerk asked her the first time.

“No,” she said.

He asked again the next time. And the time after that.

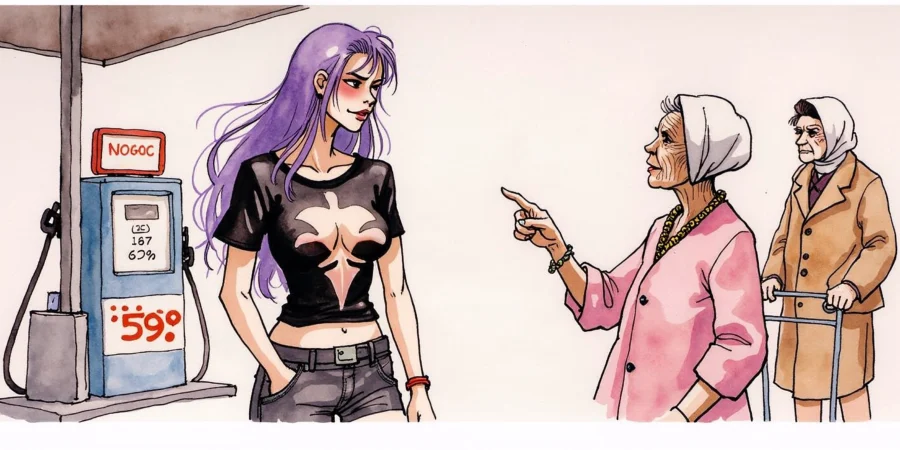

At the gas station, an old elderly woman wearing a babushka finally dropped the pretense.

“You don’t belong here,” the woman said, not unkindly—just confidently, like she was stating the weather. “What kind of lady dresses like this!” the woman proclaimed while pointing at her and looking her up and down.

The city girl stared at her for a long moment. Then smiled.

“That’s cool, but I didn’t ask.”

Back at the farm, she held it together until she didn’t.

“I’m tired,” she said, pacing the kitchen. “I don’t fit anywhere. In the city I’m too loud, too weird, too much. Here I’m a walking red flag with eyeliner.”

He leaned against the counter, dusty hands folded, listening like this mattered because it did.

“People been wrong about me my whole life,” he said. “They survive it. I do too.”

She stopped pacing.

“That’s it?” she asked.

He shrugged. “You don’t owe anyone palatability.”

She kissed him hard, sudden and grateful, like someone who’d been holding their breath without realizing it.

Moving In, Standing Out

She moved in with more boxes than necessary and opinions about where everything should go.

The farmhouse adjusted.

So did he.

The nursing home she got a job at didn’t know what to make of her. Tattoos. Piercings. Hair that changed color without warning. Doris, the unofficial ringleader of disapproval, made her feelings clear immediately.

“She looks like trouble,” Doris announced.

“She’s been doing a very good job,” another resident replied.

Doris sniffed. “So did my second husband. Still didn’t trust him.”

She worked hard. Stayed late. Learned names. Learned stories. Held hands when people cried and didn’t rush when they rambled. Slowly, the walls lowered.

Doris eventually allowed her to bring her coffee.

That was respect.

The City Calls Back

She missed the noise. Missed the anonymity. Missed walking into places where no one cared what she looked like because everyone looked like something. At a concert, packed shoulder to shoulder, she felt alive again in a way the quiet sometimes couldn’t touch.

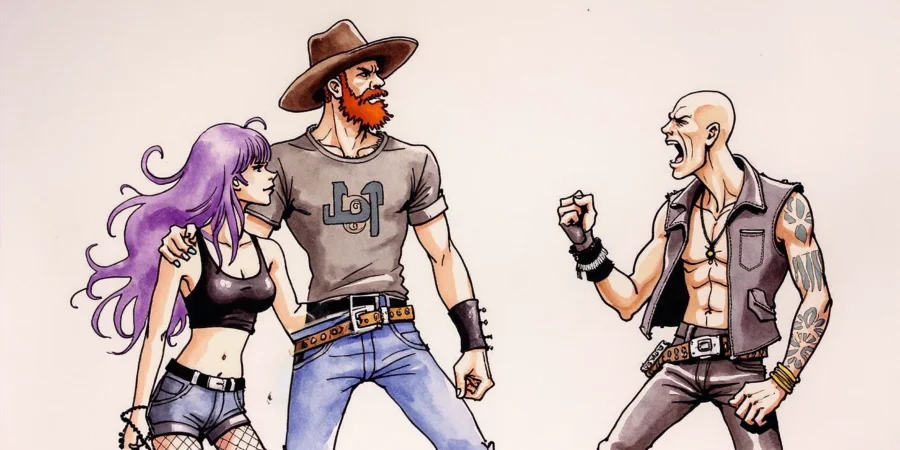

That’s when her ex-boyfriend showed up while they were at a Cannibal Corpse concert, and she forgot all of that in an instant and wanted to be back on the farm.

Smug. Loud. Drunk enough to be brave, he addressed the cowboy’s presence immediately.

“Nice costume,” he said, eyeing the cowboy. “You lose a bet, guy?”

The cowboy said nothing, instead he just eyeballed the man.

That made it worse.

Words escalated. Pride flared. Fists followed.

They couple was thrown out of the concert laughing, bruised, adrenaline buzzing.

Then they sat down on the curb, city lights humming around them, and she asked it.

“Have you ever thought of living here?”

With a laugh, he responded “What, so I could deal with that every night?”

He stared at the pavement. Thinking about how much happier she had seemed back in the city.

“I could try.”

Something in his voice should’ve warned her.

The City Makes Him Smaller

The city pressed in on the heavy metal Cowboy.

Buildings blocked the sky. Streets replaced fields. His job driving a courier van paid the bills but drained him in ways he couldn’t articulate. He was used to moving at a slow pace, but not when all he can do is stare at taillights.

Kitchens were small. Meals got smaller too. He cooked less. Talked less.

She noticed.

Then the pregnancy test turned positive.

The argument was inevitable.

“Do you really want our kid growing up around those people?” she snapped.

He didn’t raise his voice.

“I grew up there,” he said. “I turned out the way I am.”

“Why?” she asked. “Why even are you the way you are?”

He thought a long time.

“Because I never let anyone tell me I couldn’t be.”

Choosing Loud

She didn’t sleep.

The city never really did either, but tonight it felt especially insistent—sirens rising and falling, someone shouting three floors down, bass leaking through a wall like a heartbeat that wasn’t hers. She lay on her back with one hand resting on her stomach, still flat, still theoretical, but already heavy with consequence.

She tried to imagine the future here.

A child learning to nap through noise. Learning early that space was something you rented, not something you owned. Learning which streets to avoid, which trains to catch, which compromises were just part of living. None of those things were wrong. She’d learned them herself. They’d shaped her, sharpened her.

But she thought of him too.

Of the way his shoulders had curled inward lately, like he was making himself smaller without realizing it. Of how he’d stopped cooking because there was no room to move without bumping into something. Of how he stared at the sky now when they visited the farm, like it might close up again if he didn’t look long enough.

She loved the city. She always had. Loved the noise, the chaos, the permission to be strange without explanation.

But she loved him more.

And maybe loving someone wasn’t about choosing the place that made you feel most alive. Maybe it was about choosing the place where the people you loved didn’t slowly disappear.

She rolled onto her side and let herself cry quietly, not because she was sad exactly, but because she was finally being honest.

In the morning, she made coffee in their too-small kitchen and waited for him to wake up. When he shuffled in, hair sticking up, eyes still tired, she didn’t soften it or dress it up.

“Let’s go home,” she said.

He froze.

“You sure?” he asked, carefully, like the words might shatter if he leaned on them.

“I don’t want you to keep shrinking,” she said. “And I don’t want our kid thinking that’s what love looks like.”

He exhaled slowly, like someone who’d been underwater longer than they realized.

“Okay,” he said. Just that. Okay.

And for the first time in months, she saw the fire flicker back into his eyes.

Tomatoes, Time, and the Long Way Around

Coming back didn’t feel like a victory parade.

No one lined the road. No one apologized. The farm was exactly as they’d left it—patient, unimpressed, quietly waiting. He liked that about it. Land didn’t hold grudges. It didn’t care why you left. It only cared what you did when you came back.

He went back to cooking almost immediately. Big meals. Too much food. The kind of cooking that assumed people would show up eventually, even if you didn’t know who yet. She teased him about it, but ate every bite.

She went back to the nursing home and pitched the garden idea again. This time, people listened.

They argued, of course. About tomatoes. About spacing. About whether cucumbers were worth the effort. But they showed up. Dug. Planted. Laughed. Doris supervised like a general.

The town softened in increments so small you could miss them if you weren’t paying attention.

A nod at the store instead of a stare. A “morning” instead of silence. Someone asking how the baby was coming along. No one said sorry. No one had to.

Their child was born on a quiet morning with rain tapping the windows and Guns N Roses playing low in the background. He held that tiny, furious, perfect person and felt something lock into place.

This was his family.

Not something given. Something built.

As the years went on, the kid grew up with dirt under their nails and ear protection at concerts. Learned early that you could like Slipknot and Willie Nelson. That boots and black nail polish were not mutually exclusive. That kindness mattered more than fitting in.

Sometimes people still stared.

He stopped noticing.

Loud Enough to Stay

The music was loud enough to carry across the fields.

Slipknot rolled out of the barn, bass thudding against open air, distortion cutting clean through the evening like a declaration. The sun dipped low, throwing gold across the pasture, cows silhouetted and utterly unconcerned.

Earl leaned on the fence, shaking his head out of habit more than irritation now.

“YOU KNOW THE COWS DON’T LIKE THAT!” he yelled.

The cowboy didn’t even pause what he was doing.

“THEY AIN’T COMPLAINED YET!” he yelled back.

She laughed, standing in the grass with their child balanced on her hip, tiny hands grabbing at her shirt. The kid bounced happily to the noise, completely unbothered by genre or expectation.

She thought about all the places she’d tried to belong before. All the versions of herself she’d sanded down to fit rooms that were never going to make space anyway. She realized something then, watching the music spill out across land that didn’t judge it.

Belonging wasn’t something you earned by behaving.

It was something you claimed by staying.

The town still wasn’t perfect. Neither were they. But the difference now was that they weren’t asking permission. They weren’t explaining themselves. They weren’t waiting for approval that might never come.

They had built a life that made sense to them—loud when it needed to be, quiet when it mattered, stubborn in all the right ways.

The heavy metal cowboy wrapped an arm around her. She leaned into him. The music played on.

And for the first time, neither of them wondered if they belonged.

They knew.